Bamboo types vary with age, species, height from ground and growing conditions

Here is something I wrote a few days ago. It caused a bit of fuss as there are people who believe strongly in bamboo for sailboat spars, however our point of view is to look at what the boat needs to perform well and then to select the bamboo (if possible) to meet the same criteria as other materials.

I live in the Philippines and have started learning slowly about the variations in bamboo.

When someone says bamboo works fine, what type of bamboo do they mean?

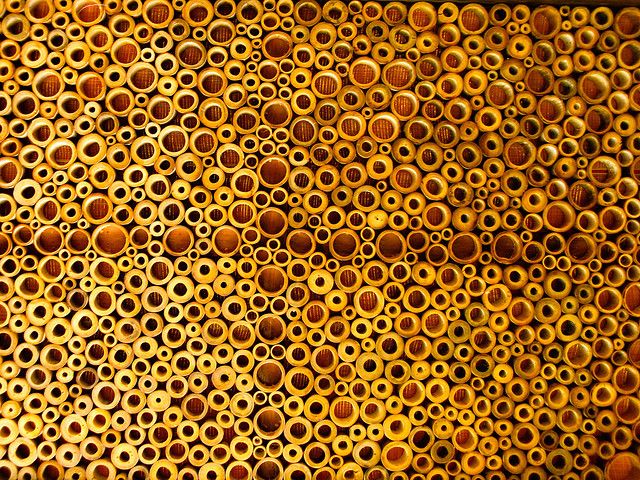

Looking closely at the photo above there is a huge variety of wall thicknesses and diameters. They vary with age, species and growing conditions. Look closely at the photo above. They range from quite thin walled to almost solid, small to large diameter.

This creates the initial problem as a professional designer. I want every boat built to work and work extremely well from when it hits the water the first time for an indefinite period.

Photo below shows the Oz Goose under pressure.

And even more pressure.

And not just for one boat. But consistently everywhere on the planet where one may wish to build one.

So from this we understand that using bamboo for masts is an experiment that is not easily repeatable. It is not possible to just think spars can be substituted with bamboo and assume that excellent performance will automatically follow.

We need to think about what are the different requirements of different spars.

So what about some guidelines?

Mythbusting, Bamboo is not light

The timber we normally use for our timber spars is recommended to be a density of roughly 30lbs per cubic foot or 500kg per cubic metre.

Typical species might be

Douglas Fir, called Oregon in Australia. 32 lbs/ft3 (510 kg/m3)

Spruce, 25 lbs/ft3 (405 kg/m3) a bit lighter but often much more expensive

White Pine 25 lbs/ft3 (400 kg/m3)

Hoop Pine 31 lbs/ft3 (500 kg/m3) is a good substitute in Australia in a country short of softwoods.

Bamboo, 31 lbs/ft3 (500 kg/m3) to 53 lbs/ft3 (850 kg/m3). On average is much more dense but has a huge range from about the right density to way too dense.

Strength of the material itself, ignoring diameter and wall thickness of a spar tends to have a close relationship with the strength of the material. Some meditation on the fact that medium density softwoods are very much preferred for spars on sailboats indicate that strength is not the strongest criterion. Otherwise we would build masts of the strongest and heaviest wood possible.

We don’t. So there is a lesson from the boatbuilding tradition. And the wrong type of bamboo will be 60 percent too heavy for the same diameter and wall thickness.

Data from the Wood Database

For the propeller heads – fracture mechanics of bamboo applies to sail boat spars

A nice little article is available here. It goes into the fracture mechanics of bamboo. Failure is normally around the nodes, the bumps between the straight parts of the bamboo. This probably means that bamboo spars will have to exceed the diameter, or percentage wall thickness or density of normal sparmaking timber.

The failure mode is interesting. Not grain compression or tensile splitting perpendicular to the grain as per timber, but longitudinal splitting where the composite moment of intertia is lost to be replaced by the much lower modulus of the same cross section broken up into smaller components decreasing stiffness suddenly with failure of the fibres through overbending.

I will quote a small part but please look up the references and the complete article to get the full picture.

For non engineering types, note the final line. In engineering terms it still means the nodes are a weak point but the structure tried to minimise that. Smart for sure, but not smart enough to fully compensate.

The results suggest that far from being a point of strength, the node may be a point of weakness when loaded in tension. Material in the node has a significantly lower tensile strength; in bending tests on intact culm lengths, failure occurs when the stress on the tensile side is exactly equal to the node’s tensile strength.

Failure occurs by longitudinal splitting: it is proposed that this may be initiated by cracks forming in the nodes. The spacing of nodes is too large to affect the stiffness and strength of the tube as a whole and also greater than the critical crack length for brittle fracture. Thus, the diaphragm and ridge structure of the node can be explained as an attempt to reinforce (to some extent, Ed) a biologically essential feature which would otherwise be a point of weakness.

BAMBOO SPARS for Oz Goose and OzRacer sailing boats

So is bamboo a hopeless case for a designer to specify? I suspect so. We can’t control diameter, wall thickness and even density has a huge variation, much greater than timber.

But I can provide some guidelines from our standard timber spars that do work on the Oz Goose. Whether you can make them work is up to your patience and the expectations you have for performance and reliability.

The spars I have the most confidence in bamboo for the yard and boom. Each spar has a specific requirement.

MAST, Strength/stiffness criterion

It is very unlikely that a bamboo mast will be strong enough without excessive diameter. Be prepared to break a few. Diameter will need to be bigger than the standard 65mm square hollow timber masts at the deck, maybe an extra five or 10mm. It should not bend much in practice. Wall thickness will have to be around 10 to 12mm to hit the right weight range which means a bit more than a quarter inch wall. Thinner walls will need more diameter.

A too bendy mast will make the halyard go slack allowing the sail to twist too much.

BOOM, stiffness criterion but with light weight

For bamboo or any material and the 12ft Oz Goose – the boom needs to be stiff particularly if set loose footed (recommended). I would expect diameter in the range of mm or 2″. this is adequate for a laced boom. A boom for a loose footed sail would be best in a thin walled section about 60 – 70mm.

YARD, measured stiffness criterion for sailboat gust response

The yard at the top of the sail has the most critical bend so we measure it. Too flexible and the boat will lack power. Too stiff and the boat will stagger and be hard to handle in gusts.

The bamboo yard needs to match the bend of a timber spar under load. I would be guessing that a diameter of around 42mm or approx 1 3/4″ would work our right, but there are many different types of bamboo.

One good trick is to buy a longer piece and choose the part that has the right bend

Methodology is to support bamboo with two supports set the same length apart as the specified yard length. Put a 10kg weight (usually a bucket with 10 litres of water) hanging in the middle. Check the bend with a stringline. It should be 30 to 40mm in the middle. The link to the WIKI at the bottom of this page has a range of real bends we measured for the Goat Island Skiff. It also anticipates a weight for a spar to be about 2.2kg or 5lbs.

If it bends more than that then move along the bamboo to a part with larger diameter and try again.

Preventing splitting at ends and compressing at mast partner

Put glass tape around the ends – two layers to stop splitting. We do this with our wooden spars too.

Put three layers 3″ 75mm wide glass cloth around the area of the mast where the deck contacts.

Large Diameter end of the yard and boom to be forward.

And here is a link to the data we collected on GIS spars. The useful bit is the recorded bends of the yard recorded in a table. Set up two trestles the distance apart of the finished spar. Hang a 10kg weight (bucket with 10 litres of water in it in the middle of the spar and measure deflection with a string line.